In 1950, Hjördis tried to describe the intensity of meeting and falling in love with David Niven.

“These sorts of things often happen when you are least prepared. As soon as we first saw each other, we both had that strange feeling of having known each other all our lives. Everything seemed to be perfectly clear between us at once. There was no doubt in either of us – we were made for each other.”

“The feeling of meeting the right person is probably the most wonderful thing that can happen to a human being. I still think it’s completely unbelievable that I’ve experienced it.”

David and Hjördis’ relationship deepened and at speed. “All that week I saw him every day. One of those days he said to me: ‘Come along to see me on the set this afternoon.'”

“There were two little boys in his dressing room when I arrived. They were sweet. David was five, and Jamie was nearly three. We played all sorts of silly games together, dressing up in fancy hats and clothes we found about the set. I noticed David watching us quizzically.” [Was he ticking a clipboard Hjördis?]

“Yet somehow, it never really sank into my consciousness that these were David’s children.”

“He was the only person in focus for me at that moment. Anything else was blurred, vague and out of focus. It was all like a lovely dream.”

The same may have been true for David.

Modern Screen magazine repeated a story that had just been added to his repertoire: “There’s a story he likes to tell about the painter, Vasco Lazzolo (who specialised in painting beautiful women), who was strolling down Curzon Street, London, on his way to a party at Sir Alexander Korda’s. An old flower seller on the first corner stopped him and offered her first bunch of early spring flowers. He bought them, smiling. ‘I shall give these to the first really beautiful woman I meet…’ Later, at the party, some of the guests noticed Hjördis holding flowers, but only a few knew why.”

Jazz after midnight

Damernas Värld neatly summed up the time. “Both had received thorns from life, wounds that were not yet fully healed. Hjördis was divorced after marriage to ‘Sweden’s number one playboy’ Carl-Gustaf Tersmeden, whom she liked very much as a person but could not be married to. David Niven had lost his wife in a tragic accident in Hollywood when their boys were very small. Together, they could suddenly laugh again, at each other and with each other.”

“He asked me down to stay with an elderly woman friend in the country*. “I think now that he wanted her to look me over for him. I must have met with her approval for about ten o’clock she said: ‘I must go to bed. I hope you don’t mind if I leave you two children alone.'”

*Apparently Yorkshire.

“We stayed up until well after midnight, talking and listening to jazz records. As always, David let me do most of the talking. He seemed preoccupied as if he had something on his mind.”

“While he was away from me, putting on a record, he said: ‘I must go back to California in a few days.’ And then, terribly awkwardly, and terribly shyly, almost off-hand and detached, he said: ‘I don’t want to leave you behind.'”

“Then it all came out in a rush. ‘Darling, will you marry me?'”

Speaking on 13th January 1948, the day before her wedding day, Hjördis mentioned that the proposal came one month after she and David first met. (David’s stories of the proposal coming after only one week appeared later.)

“I said ‘Yes, of course,’ and tried to be as restrained about it as he was. Inwardly, I was immensely thrilled and excited, not knowing – or caring – what my answer meant, certainly never realising for a moment what I was taking on.”

In her 1960 memoirs, serialised with her Swedish readers in mind, Hjördis mentioned: “I wanted to say ‘Yes’ on the spot, but knew I had other things to resolve first. I asked for a few days of reflection.”

“I remember feeling anxious. I had to call Tersan and tell him that I was going to get married. I waited until I had received the papers. Then I called.”

In 1985, Hjördis told Sheridan Morley: “I said, ‘I’m going to get married again’, and he hung up the phone, so I had to call him back because I didn’t want him just to read about it.”

“I talked it over with him. I knew it wasn’t worth us trying again. I knew I had finally met the right man for me.”

In 1963, Hjordis went for a more dramatic variation of the phone call:

“‘I’ll get over there and put an end to it!’ shouted Tersan into the telephone receiver in Stockholm.”

“‘You can’t. I’m getting married today,’ I replied.”

“Tersan was so nice. He was good. He was carefree. What an impossible combination! The carefree don’t always have it easy, and neither do the good. They have no way to take the blows when they need to. We parted as friends and remained friends.”

“I never saw him again.”

Fast-forward Wedding preparations

“It was a busy week for us. We had to arrange all the paperwork for the wedding, the reception… a thousand things.”

David ‘s ‘The Moon’s A Balloon’ best-seller from 1971 describes the red tape encountered while trying to organise a quick marriage, as well as tightening up the narrative of Hjördis’ recent activities:

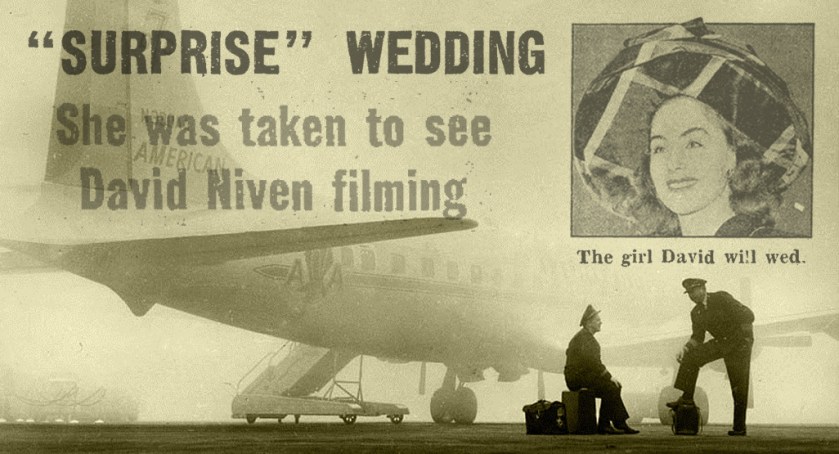

“She was Swedish, which posed all sorts of strange problems with the marriage authorities. Also, she didn’t speak English too well which helped matters not at all when it came to explaining to them that she had landed in England en route from America to Sweden, the plane had been grounded because of sudden fog at London Airport, and a friend on board invited her to visit a film studio.”

“I lost my Swedish nationality on our marriage, which I often think is a pity. I learned afterwards that I could have remained a Swedish citizen and had dual nationality if I had pressed for it, but nobody told me.”

The day before the wedding, David showed great sensitivity by bringing Hjördis to meet Primmie’s parents, William and Lady Kathleen Rollo at their London residence in Farm Street, Mayfair.

“David was first married to an English woman, Primula Rollo, who had a tragic accident in Hollywood when their two boys were very small. David was very fond of Mr. Rollo, an adorable man.”

Cholly Knickerbocker gets it wrong

In addition to contacting Carl Gustaf, Hjördis called Igor Cassini, according to Igor. In his 1977 autobiography, he wrote: “Hjördis took a vacation in Europe. The trip turned out beautifully. She met the recently widowed David Niven. Hjördis called me from England to give me the aut-aut [either/or ultimatum], either I got free or she would not be any more. Both she and I did the right thing.”

Hjördis most probably called Igor before meeting David Niven, as a snippet appeared in the 28th December 1947 ‘Cholly Knickerbocker’ column, tacked onto a piece about Swedish blue-bloods partying in New York: “Carl Tersmeden of the wealthy Swedish pulp family, and his estranged wife Hjördis, are back together again in Stockholm.”

Wrong and wrong. [Before you feel too sorry for poor old Carl Gustaf, bear in mind that with Hjördis there were consequences for infidelity.]

On Thursday 4th December 1947, the likely date that Hjördis met David Niven, US newspapers announced that Igor Cassini was set to wed a young US socialite, Elizabeth Darrah Waters. He had obviously been active in her absence [and most probably before]. The marriage took place on 22nd January 1948, one week after Hjördis and David. All of these shiny new marriage certificates flying around high society certainly put David’s “why wait?” wedding plans into perspective. In short, it was a case of marrying her before someone else did.

“The strange thing is, the last thing on my mind was initiating some kind of love at that time. I had completely different plans for my life and was eventually going to go back to Sweden. I never did complete that journey.”

“As each day went by, I became increasingly nervous. David promised me that we would have a quiet wedding, joined only by a few friends afterwards. But I knew how difficult it was for movie stars to maintain their privacy.”

A farewell to Carl Gustaf Tersmeden

Although an imminent third union was reported from the French Riviera in 1956 (to a rich American woman called ‘Mrs Hudson’), Carl Gustaf doesn’t seem to have remarried.

Instead, he pushed the yacht out and lived a rootless millionaire playboy lifestyle. His post-Hjördis life seems hedonistic but not entirely happy.

Described as “sad, and recently abandoned by the model Hjördis Genberg” Carl Gustaf took an interest in an 18-year-old called Doris Hopp, and gave her an introduction to Stockholm society. She quickly saw that there was money to be made and subsequently became Sweden’s most infamous brothel madam.

Around the same time he also took “quite an interest” in another teenager, the Swedish aristocrat Gunilla Von Post. She later described him as “a charming and generous bon vivant”.

If you recognise Ms Von Post’s name, yes, she had a fling with John F Kennedy, both before and after his marriage to Jacqueline.

“She was not the first – or indeed the last – to fall for the charms of a man notorious for his sketchy grasp of the obligations of matrimony,” The Telegraph wrote. Unfortunately, this is not the last mention of JFK and his sketchy grasping.

In 1949, Carl Gustaf was referred to in the Swedish press as “Sweden’s Bertie Wooster” (not exactly a compliment) and in the 1950s as Sweden’s undisputed number one playboy.

An American Newsday article in August 1949 labelled him as: “a dashing Swedish pulp paper prince [try saying that with a mouthful of tacks] temporarily at liberty after shedding his second wife Hgordes Jenberg [who?]”

“He spends about six months a year in the United States selling wood pulp to US newspaper publishers.” Ironically, some of the resulting paper was used to tattle on his playboy lifestyle, ultimately just to call him fat and sad.

In addition to selling pulp, Carl had ‘Symfoni’ shipped across the Atlantic for recreational sailing around Long Island and continued his wintering with American East Coast society, providing the gossip columnists with plenty of ammunition.

In 1949, he was spotted in Palm Beach by Igor Cassini (probably from a safe distance) with Swedish-born actress Elizabeth Berge, and in 1950 with ex-model socialite Mildred ‘Brownie’ Schrafft, the wife of a business associate, chocolate baron George Schrafft. [Disappointingly, ‘Brownie’ came from her maiden name, Brown, and had nothing to do with chocolate brownies.]

Also, in 1950, Igor cheekily named Carl as the possible cause of a divorce between an unnamed young New York society couple. This was a bit rich, considering that he had contributed generously to Carl’s divorce three years earlier.

In May 1951 Igor reported that Carl had “a new sweet tooth”, this time with Cary Grant’s 1947 fling, the John Powers model Betty Hensel.

Scrolling forward to May 1952, Carl was listed in another short-term Palm Beach relationship, this time with Eve Wolfe, the estranged wife of Ohio newspaper publisher Ed Wolfe. In her report of the romance, Miami society columnist “Suzy” described Carl as a “stout Swedish socialite.”

Suzy had already well and truly skewered poor old Carl early in the year with an acidic piece that can’t have been easy for him to shrug off:

“Carl Tersmeden, the blonde portly man-about-town may wander along Gold Coast smart spots with various and sundry good-looking gals, but he’ll never find one as lovely as his ex-wife, the former Hjördis Tersmeden, who is now married to David Niven. Carl knows it too.” [Big ouch]

Suzy’s real name was Aileen Mehle. In 1963, she took over Igor Cassini’s ‘Cholly Knickerbocker’ column in The New York Journal-American and changed her writing name to Suzy Knickerbocker.

After 1952, Carl retreated to Paris and then his yacht in the south of France, where he entertained top-drawer playboys and playgirls such as Zsa Zsa Gabor, Porfirio Rubirosa, Aly Khan, and David Niven’s old cohort Errol Flynn.

Carl returned to Sweden in March 1957, where he died on 20th April 1957 aged just 40, ten years after his divorce from Hjördis. His death was afforded one small report in the US press, ironically by Igor Cassini:

“International society was shocked to hear that wealthy Swedish playboy Carl Tersmeden, an ex-husband of the present Mrs David Niven died of a heart attack in Stockholm.”

Next page: South Kensington Registry Office 1948